41. Behavioural Economics

Introduction

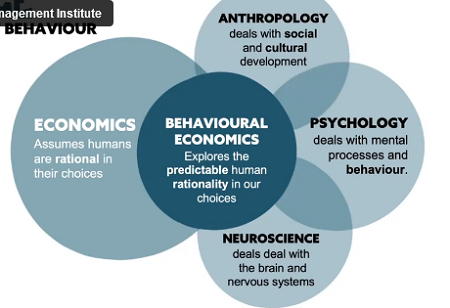

Behavioural economics is grounded in science and helps you to understand how people think, which enables you to better to predict outcomes and to design for successful outcomes, especially in behavioural change.

Science of behaviour is based on 2 disciplines coming together, ie

i) economics (traditionally it assumed that humans are always rational in their choices)

ii) psychology (deals with mental processes and behaviours)

In the 1960s, some economists realised that not all human behaviour was rational. With the help of psychologists, they developed a new field called behavioural economics (explores the predictable human rationality and irrationality in our choices and decision-making).

Later on, the fields of anthropology (deals with social and cultural development) and neuroscience (deals with the brain and nervous system) were also added to the behavioural economics mix

(source: Edwina Pike, 2022)

Behind behavioural economics is the prospect theory, ie

"...describing how individuals make a choice between probabilistic alternatives where risk is involved and the probability of different outcomes is unknown..."

James Chen, 2022

Losses and gains are valued differently:

"...linked with loss aversion, endowment effect, sunken costs fallacy and status quo bias; with loss being valued higher than gains..."

Arun Pradhan, 2019

(for more detail, see other parts of the Knowledge Base)

Losses have a higher emotional impact than gains.

It is also linked with certainty and isolation:

- you prefer certain outcomes over probable ones (certainty)

- individuals cancel out similar information when making a decision (isolation)

In addition to prospect theory, there is

- paradox of choice (the more choice, the lower the conversion rate)

- gold gradient effect (eg return visit coupons that are already partly stamped have a more positive impact on encouraging return visits than completely unstamped coupons)

- hyperbolic discounting (prefer immediate rewards, ie you value a reward in the short term more than in the medium or long-term).

People have more of a chance of making good decisions when

"...they are experienced, have good information and receive prompt feedback......they do less well in contexts in which they are inexperienced and poorly informed, and in which feedback is slow or infrequent..."

Richard Thaler et al, 2021