Some Types of Cognitive Biases

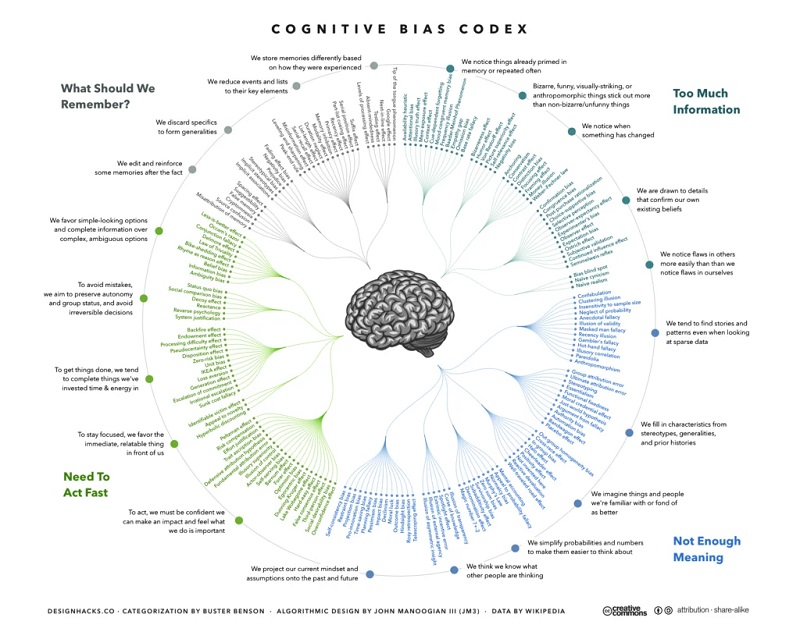

Around 150 cognitive biases can be divided into 4 categories, ie

i) information (what needs to be filtered)

ii) meaning (connecting dots and filling in the gaps with what we think we know)

iii) speed (making decisions based on new information)

iv) memory (as you can't remember everything, you need to be selective)

(source: Gust de Backer, 2022)

"...1. Information

Humans have to process an enormous amount of information every day, but in the past people also had to do this. Now we have built-in tricks to filter information.

1.1 We notice things that are already imprinted in memory or that are repeated often

You are more likely to recognize things if you have experienced them recently. Consider:

- Availability Heuristic: memories that happened recently outweigh memories with more impact from the past.

- Attentional Bias: subconsciously we choose points to which we pay attention. A smoker is more likely to notice other people smoking.

- Illusory Truth Effect: by repeatedly hearing false information we come to believe it is the truth.

- Mere Exposure Effect: we give preference to things we have seen more often or are familiar with.

- Context Effect: the context in which we see something affects how we look at something and what value we place on it.

- Cue-Dependent Forgetting: remembering certain things by thinking of equivalent memories.

- Frequency Ilussion / Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon: if you see something once and start paying attention to it, you will see it more often, if you buy a car, you will see the same car more often.

- Empathy Gap: we are bad at empathizing with others, but expect others to empathize with us.

1.2 Bizarre, funny or visually striking things grab our attention

We pay more attention to things that are striking; as a result we often skip over information that we label as normal or expected.

- Bizarreness Effect: we remember bizarre things better than normal things.

- Humor Effect: we remember things with humor better than without.

- Von Restorff Effect: we remember one striking thing in a series of equivalent things better.

- Picture Superiority Effect: we remember pictures better than text.

- Self-Reference Effect: things we feel related to we remember better.

- Negativity Bias: people are more likely to be attracted to negativity.

1.3 We notice when something has changed

The value we give to change lies in whether it has changed positively or negatively, rather than presenting it as a change in itself.

- Anchoring: we hammer down on the first piece of information we receive, we interpret new information from the first piece of information.

- Conservatism Bias: we do not sufficiently revise our opinion when we’re shown new evidence.

- Contrast Effect: red dots on a white background appear black, but on a grey background they appear red.

- Distinction Bias: we place more value on the difference between two options when comparing them than we would if we were evaluating them separately.

- Framing Effect: people are influenced by the way information is presented; 20% fat or 80% fat free.

1.4 We are attracted to details that confirm our own beliefs

We are not always very open to feedback and refuse to believe certain things that go against our own beliefs.

- Confirmation Bias / Continued Influence: we unconsciously focus on things that align with what we believe.

- Post-Purchase Rationalization / Choice-Supportive Bias: after making a choice, we overvalue positive attributes of the choice and forget the negative attributes of the choice.

- Selective Perception: we ignore certain things if they are not in line with what we believe.

- Observer-Expectancy Effect: people behave differently when someone is watching them.

- Experimenter’s Bias / Observer Effect: a researcher can, without realizing it, influence his participants to go in a certain direction.

- Ostrich Effect: ignoring negative things like feedback or criticism, burying your head in the sand.

- Semmelweis Reflex: rejecting new evidence because it doesn’t match current norms, beliefs and paradigms.

1.5 We notice faults in others more easily than in ourselves

Mistakes are not always in others, but also in ourselves. Unfortunately, we notice mistakes in others faster than in ourselves.

- Naïve Cynicism: we think people are more selfish than they really are.

- Naïve Realism / Bias Blind Spot: we think we see the world objectively and that others who don’t see it the same way are misinformed, irrational or biased.

2. Meaning

There is too much information to process, we take in as much information as we can and fill in the gaps in between with what we think we know.

2.1 We see patterns and stories, even when there is hardly any data

People look for patterns, and we see patterns even when they’re not there.

- Clustering Illusion: we think we see clusters when objects are placed randomly.

- Insensitivity to Sample Size: looking at a statistic from a test without considering the test size. In fact, variation is greater in smaller test sizes.

- Neglect of Probability: neglecting a relatively small chance that something will happen. For example, not wearing a seatbelt because there is a small chance of an accident happening.

- Anecdotal Fallacy: evidence based entirely on personal experience without real evidence.

- Illusion of Validity: we overestimate our ability to make decisions based on data.

- Gambler’s Fallacy: thinking that something will not happen soon in the future if it has happened many times in the past.

- Hot-Hand Fallacy: thinking that a person with success in the past is also going to have success in the future.

- Illusory Correlation: seeing a correlation between two variables that are unrelated.

- Pareidolia: seeing patterns or objects in something that are not there. For example, seeing shapes in the clouds.

- Anthropomorphism: personifying an animal or object, for example, a sun with a face.

2.2 We supplement properties from stereotypes, generalities and past events

When we (think we) have information about something, we associate it with a certain thing or person. So we then supplement the unknown information with what we already know.

- Group Attribution Error: thinking that the characteristics of one person reflect the characteristics of the whole group.

- Stereotyping: a generalized belief about a certain category of people.

- Essentialism: believing that an object must have certain properties for its identity.

- Functional Fixedness: using an object only for the way it traditionally should be used.

- Self-licensing: increased self-confidence makes an individual more likely to engage in undesirable behaviour because they believe there are no consequences.

- Just-World Hypothesis: thinking that the world is fair and that everyone gets what is coming to them. People who do good things will be rewarded and people who do bad things will be punished.

- Authority Bias: we value the opinion of an acknowledged authority; people follow authorities rather quickly.

- Automation Bias: preferring suggestions made by an automated system, even if a non-automated suggestion is better.

- Bandwagon Effect: adopting a certain behaviour, belief, style or attitude because others do it.

- Placebo: believing something works is often enough to make a remedy work.

2.3 We judge people or things better if we are familiar with them

We prefer people or things we already know, in fact, we attach a certain value and quality to them.

- Cross-Race Effect: we recognize faces of our own race better than faces of another race.

- In-Group Favoritism: we prefer people in our own group rather than outside the group.

- Halo Effect: people, companies, brands or products are judged by their past performance or personality, even if the current or future situation has nothing to do with the past.

- Cheerleader Effect: individual people are more attractive in a group.

- Positivity Effect: we tend to bring positive news.

- Not Invented Here: not buying or adopting ideas, products, research, standards or knowledge because they come from external sources.

- Reactive Devaluation: undervaluing something coming from someone who stands for something different from you.

- Well-Traveled Road Effect: estimating route times differently because you are unfamiliar with the route. Routes travelled more often seem to take less time than new routes.

2.4 We simplify probabilities and numbers to make them easier

Humans are bad at maths so we often make mistakes in calculating the probability of whether something will happen.

- Mental Accounting: we put a value on something we have earned that is based on how we earned it; for example, did we have to work hard for it?

- Appeal to Probability Fallacy/Murphy’s Law: we assume that if there is a chance of something happening that it will actually happen.

- Normalcy Bias: we underestimate things that might come, sometimes we don’t even believe they are going to happen. For example, think of a car accident or a natural disaster.

- Zero Sum Bias: thinking that if one thing goes up that another will go down.

- Survivorship Bias: looking only at the successful subset in a larger group in which many have failed.

- Subadditivity Effect: judging the probability of a whole as less than the probability of separate parts.

- Denomination Effect: we are less likely to spend money if it is large bill money, and are more likely to spend lots of coins to the same value.

2.5 We think we know what others are thinking

Sometimes we think others know the same as we do and sometimes we think we know what others think.

- Illusion of Transparency: we assume that others know how we feel.

- Curse of Knowledge: while communicating with others, we think they know the same as us.

- Spotlight Effect: people feel watched much more than they are actually watched.

- Extrinsic Incentives Bias: thinking that others are more motivated to do something if they receive an extrinsic reward (such as money) than for an intrinsic reward (such as learning a new skill).

- Illusion of External Agency: thinking that good and positive things happen because of outside influences.

- Illusion of Assymetric Insight: we think we know others better than others know themselves.

2.6 We look to the past and future with our current thinking

We are bad at estimating how quickly or slowly certain things will happen.

- Rosy Retrospection: people judge the past as more positive than the present.

- Hindsight Bias: we think past events were more predictable than they actually were.

- Outcome Bias: evaluating a decision when the outcome is already known.

- Impact Bias / Affective Forecasting: we find it difficult to estimate how much emotional impact certain actions or events will have on us.

- Optimism Bias: thinking that a negative event is less likely to occur to ourselves.

- Planning Fallacy: we underestimate the time a task will actually take from us to complete; outsiders overestimate the time others need for a task.

- Pro-innovation Bias: not seeing the limitations and weaknesses of a particular innovation, only wanting to implement the innovation.

- Restraint Bias: we overestimate our ability to control impulsive behaviour, and don’t think we’ll get addicted to something.

3. Speed

We are limited by time and information, but we can’t let that stop us from taking action. With each new piece of information, we start looking for applications.

3.1 To make an impact we need to be confident and feel that what we are doing is important

Often we have too much self-confidence, but without self-confidence we would not take action.

- Overconfidence Effect: we think we make better decisions than we actually do, especially if our self-confidence is high.

- Social Desirability Bias: in conversation with others, we answer questions in a way we think will make the other person happy, personally and professionally.

- Third-person Effect: we overestimate the effect that mass communication has on others, but underestimate the same effect on ourselves.

- False Consensus Effect: we think our own behaviour and the choices we make are normal, especially given the circumstances in which they occur.

- Hard-Easy Effect: we think that a difficult task will be a success faster than an easy task.

- Dunning-Kruger Effect: people without skills overestimate their own ability, people with lots of skills underestimate their own ability.

- Egocentric Bias: we place too much value on our own perspective and opinion.

- Optimism Bias: thinking that a negative event is less likely to occur to ourselves.

- Barnum Effect / Forer Effect: thinking a text is about you when the text usage is so vague and general that it applies to a large group of people; this is often used in horoscopes.

- Self-serving Bias: we want to keep our self-esteem high, therefore we think that success comes from our own ability and we write off mistakes to external factors.

- Illusion of Control: we overestimate our ability to influence certain events.

- Illusory Superiority: we overestimate our own ability and our own qualities over those of others.

- Trait Ascription Bias: we consider ourselves unpredictable in terms of personality, behaviour and mood while we consider others predictable.

- Effort Justification: the value we place on an outcome is determined by the energy we had to put into it.

- Risk Compensation: we become more cautious when risk is high and become less cautious when we feel confident and secure.

3.2 To stay focused, we prefer known things that we can do immediately

We value things in the present more than in the future.

- Hyperbolic Discounting / Instant Gratification: we prefer a reward if we get it sooner, we unconsciously attach a discount to a reward that is further away.

- Appeal to Novelty: underestimate the status quo and think that new is always better.

- Identifiable Victim Effect: we are more willing to help if we see one victim than if a large group needs the same help.

3.3 We are more likely to complete things if we have already invested time and energy in them

Something that moves will keep moving was Newton’s first law of motion. We want to finish things we have already started, even if we have found plenty of reasons to stop.

- Zeigarnik Effect: we remember unfinished tasks better than completed tasks.

- Sunk Cost Fallacy: something paid for that cannot be reversed. Past costs incurred are no longer relevant to future decisions.

- Irrational Escalation: continuing what you were doing despite having negative outcomes because it is in line with past decisions and actions.

- Generation Effect: we remember things better when we have thought of them ourselves rather than having read them somewhere.

- Loss Aversion / Disposition Effect: we are more afraid of losing something than we are motivated to win something.

- IKEA Effect: we place more value on products that we have helped create.

- Zero-Risk Bias: we prefer to reduce risk on subcomponents than remove a greater amount of risk over the whole.

- Processing Difficulty Effect: we remember information better when we have to put in work to understand it.

- Endowment Effect: we are more likely to keep something we already have than we would be to get the same thing if we didn’t already have it.

- Backfire Effect: if we reject evidence that goes against what we believe then we will believe even more strongly in what we already believe.

3.4 To avoid mistakes and maintain status in a group we avoid irreversible decisions

We like choices without risk or that confirm the status quo.

- Reverse Psychology/Reactance: promotionof a belief or behaviour that is opposite to the desired behaviour, the person is then more inclined to start doing the opposite (the desired).

- Decoy Effect: people tend to make a certain choice between two options if given a third, not interesting, option.

- Social Comparison Effect: we tend to dislike people if they are physically or mentally better than us.

3.5 We prefer simple choices with lots of information, rather than the other way around

We prefer to do something that is quick and simple rather than something that is difficult because we think we can spend our time better with the quick and easy tasks.

- Less-is-better Effect: we perceive a €50 scarf has more value when scarves are between €5 and €50 than a €55 coat when coats are between €50 and €500.

- Conjunction Fallacy: we think something is more likely to happen if it contains a specific condition (loses the first set but then wins the match) than if it is presented as a general event (wins the match).

- Law of Triviality: focusing on non-important details (whether or not to put ‘,’ in a certain spot) when there are much more important things (campaign budget) to discuss.

- Rhyme-as-reason Effect: we are more likely to believe things if they are rhymed.

- Belief Bias: we find arguments stronger if they support what we already believe.

- Information Bias: more information is not always better; we think we make better choices when we have more information, but that is often not the case.

- Ambiguity Bias: we prefer options that have a higher probability of success than options whose probability of success is unknown.

4. Remembering

There is so much information, so we only remember what will help us in the future.

4.1 We modify memories

Memories can get stronger, we can mix up details and sometimes we add things ourselves.

- Misattribution of Memory: we sometimes do not remember things as they happened.

- Source Confusion: remembering things differently after hearing other people talk about the same event.

- Cryptomnesia: we see something somewhere and later remember it as something we did or made ourselves.

- False Memory: remembering things we think we did, but which in fact never happened.

- Suggestibility: we are willing to accept suggestions from others and build on them for actions; if someone says something often enough we start to believe in it.

- Spacing Effect: by putting more time between, for example, studies sessions we remember things better because the information gets into our long-term memory.

4.2 We avoid specific things to add generality

Out of necessity, we avoid specific thing rather than generality, but there can be consequences for this.

- Fading Affect Bias: memories with negative associations are forgotten faster than positive memories.

- Negativity Bias: we are much more attracted to negativity.

- Prejudice / Stereotypical Bias: we prejudge people based on the group we put them in; for example, their political affiliation, gender, age, religion or perhaps race.

4.3 We reduce events and lists to their most important elements

Lists and events are not easy to generalize, so we extract only the most interesting parts.

- Serial-position Effect: we remember more accurately the first and last items in a list; middle items are remembered less accurately.

- Recency Effect: we best remember things that happened most recently.

- Primacy Effect: we best remember information presented first.

- Memory Inhibition: we don’t remember much of irrelevant information.

- Modality Effect: the way knowledge is presented contributes to how well the knowledge is remembered. In general, knowledge is better transferred using a visual presentation.

- Duration Neglect: how painful or unpleasant an experience is remembered will not be determined by the duration of this pain - or unpleasantness.

- Serial Recall Effect: our ability to recall items or events in order.

- Misinformation Effect: our ability to adjust memories of events after hearing information after the event has occurred.

- Peak-end Rule: the value we place on a memory is not determined by the average of that event, but is instead determined by its peak and end.

4.4 We store memories based on how we experience events

The value of information has little to do with how we store memories; instead it is more down to factors such as what is happening around us, how the information is presented, how easily we can retrieve the information, etc.

- Levels-of-Processing Effect: the better we analyze something and the more energy we put into the information, the better we remember it.

- Absent-mindedness: people have three reasons for not paying attention or forgetting things:

- Lack of attention

- Tunnel vision on one item and ignoring the rest

- Distraction by external factors

- Testing Effect: things are sent to our long-term memory faster if we have to recall/remember certain things more often.

- Next-in-Line Effect: things we hear/see/experience just before we need to perform we remember worse than things further in advance or afterwards.

- Google Effect: we forget information that we can easily look up.

- Tip of the Tongue Phenomenon: not being able to bring up a particular word or phrase..."

Gust de Backer, 2022